Rummaging through the archives, we stumbled across David Patten’s fascinating research into Dartmouth Park. He uncovered a relationship between the design of the park, the Pythagorean Y Theory and the Fibonacci Sequence. This armed us with important historical information to support the design process for the Pavilion.

David wrote the following text which supported our feasibility study submitted to SMBC and the HLF.

Parks for People define heritage value as “everything tangible and intangible that we have inherited from the past, and value enough to want to share and sustain for the future”. So what have we inherited from the original Park designer(s) that we may want to share and sustain into the future?

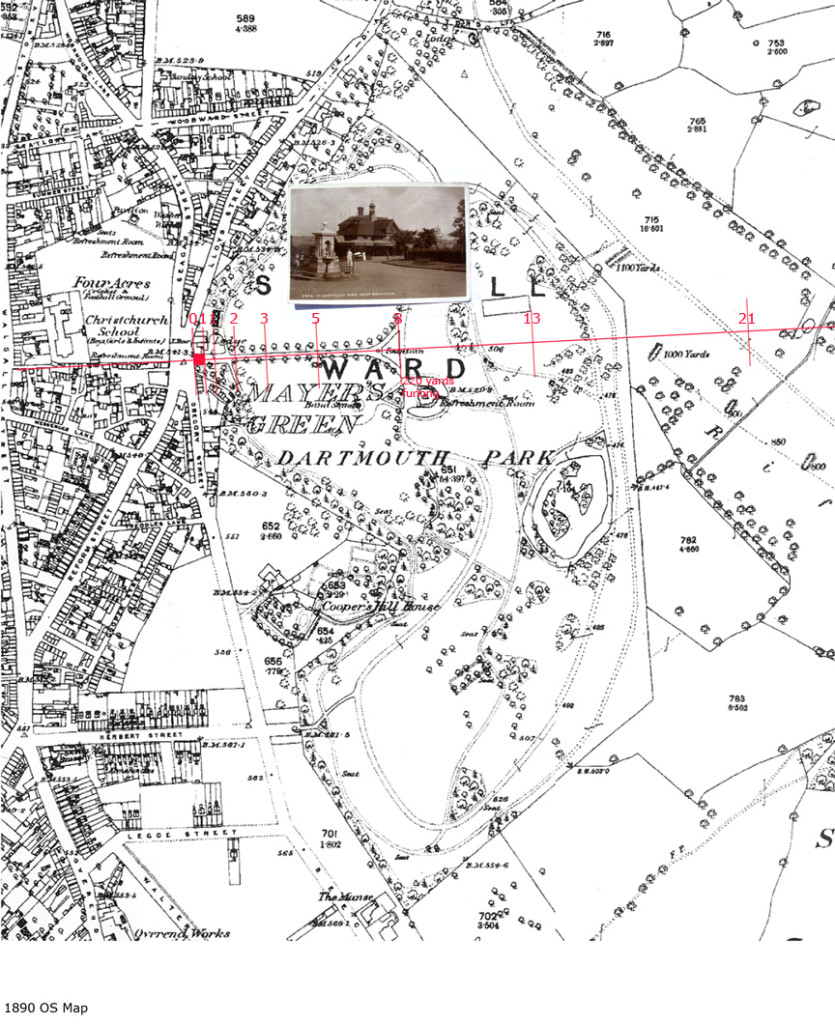

Landscape Gardener John Maclean was delivering the Park user to a viewing point almost at the centre of the park, and the end of an Avenue measuring one furlong in length. This Avenue is set 3 degrees off the exact East – West alignment for reasons we don’t know.

This Avenue starts as an Extended Threshold for a distance of just over 1.5 chains [a measure of length equivalent to a chain (66 ft)] from the Park gates to the N – S path. This extended Threshold is 11 yards (2 poles) wide. The Avenue path then continues at a width of 5.5 yards (1 pole) wide, with tree planting either side reinstating the 11 yards (2 poles) width of the initial Threshold. These two widths, 11 yards and 5.5 yards relate to the widths of the two gate types – the carriage gate and the two flanking pedestrian gates.

A drinking fountain donated by the Earl of Dartmouth was located along the Avenue at 9 chains distance from the Park gates, at the point where the Avenue splits left (North) and right (South).

The later War Memorial is located just beyond the half-way point of the one furlong Avenue sometime after the Avenue was widened to take up the full 11 yard width. Also, at some later date (sometime between 1919 and 1939) a new N – S path, at almost the same width as the Avenue, was located about 3 chains distance from the Park gates.

Maclean’s design intention seems to have been to create a vista – “a long narrow view, esp. down avenue” – that terminated, where the land fell away at the centre of the Park, to reveal a panoramic view.

As Land Agent Exsuperius Weston Turnor commented: “…naturally so fine a situation with such good views and beautifully undulating varieties of the ground…”.

Moving Through The Landscape

On the whole, it can be seen that Maclean’s design for Dartmouth Park is an enhancement of the the existing landscape asset, with additional planting as necessary to achieve an agreed English landscape experience, plus driveways and footpaths necessary to allow the site to function as a public park.

This moving through (driving or walking) what appears to be a ‘natural’ landscape is at the core of the English landscape aesthetic, and clearly guides Maclean’s design for Dartmouth Park (and earlier for Williamson Park in Lancaster). Dartmouth Park is arranged as set piece framed scenes or views, revealed or hidden by visitor movement in real time and space.

Essentially, this is the vocabulary and syntax of landscape painting made real, and the artistry of ‘natural’ landscape design lies in how scenes are framed and set up. It should be noted here that John Maclean always described himself as a ‘landscape gardener’, a term invented by Humphrey Repton to explain the skills required for successful landscape design as “the united powers of the landscape painter and the practical gardener”.

That having been said, though, Dartmouth Park is more than the expression of the English landscape tradition – there is something else at play here.

Nothing But The View

“It led to nothing but a view at the end…[.] It was a sweet view – sweet to the eye and the mind. English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a sun bright, without being oppressive.” [Jane Austen: ‘Emma’ 1816]

The Dartmouth Park Avenue, running almost exactly west to east, would have delivered the visitor to a magnificent view over the River Tame valley – today this view is obscured by the dense tree canopy.

In ‘garden’ design, the use of a tree-lined avenue to emphasise vista (long, narrow view) predates, and is not essentially part of, the English landscape tradition. The avenue as strong axial line, usually aligned upon an important feature in the distance (which doesn’t seem to be the case at Dartmouth Park), was very much part of Baroque garden design in mainland Europe, particularly in Italy and France.

As a design contrivance in European formal garden design, the Avenue sits uncomfortably within the more informal (or ‘natural’) vocabulary of the English landscape tradition, as expressed elsewhere at Dartmouth Park. It certainly does not appear to be part of John Maclean’s design repertoire.

The Pythagorean ‘Y’ & The Choice of Hercules

“…theory gives fresh meaning to old places, connects the seemingly unrelated, and grounds action.” [Anne Whiston Spirn: ‘’The Language of Landscape’]

At Dartmouth Park the Avenue was designed to terminate at the fountain donated by the Earl of Dartmouth, before forking north and south to lead the visitor along the ridge line. This arrangement of a forked long, narrow path is known in garden design as a Pythagorean ‘Y’ and, unlike the rest of Dartmouth Park, is best read in plan form.

It should be kept in mind that, as a consequence of the West Bromwich Improvement Act, the creation of Dartmouth Park was about both physical AND moral improvement – “the weary toiler may delight and invigorate himself whilst moralizing on the beauties of nature so profusely spread around him”. Consequently, if understanding the design of the Park is only focused on its physical attributes (its buildings, landscaping, footpaths, etc.), a possible landscape metaphor may be overlooked.

In garden design (the original scheme for Villa d’Este at Tivoli, for example), the Pythagorean ‘Y’ is used to reference the ‘Choice of Hercules’. After pursuing the straight and uneventful path of youth and on the verge of manhood, Hercules contemplates his future when two women appear to him. One, Vice, eager and seductive, shows him a path which seems to offer easy progress to a life of indolent pleasure. The other, tall and beautiful and identified as Virtue, warns Hercules that what is truly good can only be obtained through hard effort – and only then can Hercules gain supreme glory. It should be noted that the “straight and narrow” Avenue at Dartmouth Park has increased in width over the years – it was originally designed as a narrow 6.8 yards width and its subsequent widening possibly relates to the installation of the War Memorial in the 1923.

Given the instrumental intentions behind the creation of the new Park, is it possible that a landscape metaphor taken from Xenophon’s ‘Memorabilia or Memoirs of Socrates’ was being introduced into the design as moral guidance to the Dartmouth Park visitor? It is more than likely.

In 1870, Frederick Law Olmsted [note 8] clearly linked the importance of the public park to mitigating “the special evils by which men are afflicted in towns”, and in later versions of the story of the Choice of Hercules, vice is reinterpreted as ‘active’, and virtue as ‘reflection’. Even today, we expect our public parks to give us opportunity to be active or to reflect.

They Knew Their Onions

“[the 2nd Earl] had a great fondness for the Axe, freely pruning the Sandwell Park trees. One day when he climbed one of them, some persons having business with him, were passing and being strangers personally, and doubtful if they were on the right track for the hall, seeing a plainly dressed woodman in the tree, as they supposed, shouted out “My man, can you tell us if we are going right for the Hall”. The Earl (of Dartmouth) quietly, directed them, then descending the tree rapidly, and by a short cut, reached the Hall before them to transact the business they came upon, doubtless to their surprise and confusion.” [Handsworth Chronicle 5th April 1890]

The 17th century gardens at Villa d’Este, Tivoli were dedicated to Hercules, and the central axis was terminated by a fountain at which point the visitor had to choose between paths leading left or right. Certainly the 5th Earl of Dartmouth donated the fountain that completes the arrangement of the Avenue at Dartmouth Park, and this fountain was located exactly where the path forks. Is this just coincidence, or is this indicative of an additional something beyond Turnor’s original assessment of the site’s “park-like character” and his “less is needed or even desirable”?

The Earls of Dartmouth are closely associated with landscape design and horticulture [note 9]. Sandwell Park’s ‘cultivated lawns’, praised in verse in 1767, were laid out by the 2nd Earl who had travelled with the landscape painter Richard Wilson through Italy in the mid-1750s. Wilson, sometimes recognised as the founder of the British landscape school, made 68 drawings and watercolours of the great gardens in and near Rome (including Tivoli) for the 2nd Earl’s collection.

When William Walter Legge, Viscount Lewisham MP acceded to the title the 5th Earl of Dartmouth in 1853, he began to introduce terraces, formal gardens, fountains, and new walks in to the landscape set out at Patshull by Capability Brown in 1768. In doing this, the 5th Earl of Dartmouth was ‘adjusting’ the ‘natural’ landscape design aesthetic appreciated by his ancestors by using J. C. Loudon’s ‘Principle of Recognition’ – “Any creation, to be recognised as a work of art, must be such as can never be mistaken for a work of nature”.

This shift towards Loudon’s notion of the Gardenesque, in which the 5th Earl was advised by William Broderick Thomas, the landscape gardener at Sandringham House, could be the reason why the ‘natural’ design of Dartmouth Park includes a formal avenue characteristic of the Baroque.

The Avenue As Mathematical Conundrum

“…of all is number and the belief that certain numerical relationships manifest the harmonic structure of the universe.” [Pythagorean Concept]

Baroque gardens of the 17th century make use of mathematics and science, particularly geometry, optics and perspective – and numerical relationships determine the design of the Avenue at Dartmouth Park.

Entering the Park from the Mayer’s Green entrance, the visitor passes through a wide ‘extended threshold’ that leads to the “straight and narrow” section of the Avenue. The Avenue, originally terminated by a fountain at the point where the path forks north and south, gives access to the views of the River Tame valley along the ridge line that runs north to south through the Park.

The width of the ‘extended threshold’ is 11 yards (or 2 poles), and this functions as the basic dimension by which the proportions of the Avenue can be understood.

The width of the Avenue (the “straight and narrow” part of the Pythagorean ‘Y on the 1890 OS) is the golden ratio of this basic dimension – i.e. 0.618 the width of the extended threshold (11 yards x 0.618 = 6.798 yards).

The overall distance of the axis from the Park gates to the north/south driveway along the ridge line is 220 yards or one furlong in length – this is exactly the midpoint of the original area of the Park. The natural ridge line was originally some distance short of this length, the natural topography dropping away just at the point where the Avenue begins to fork. That the overall length of the axis was extended to achieve the 220 yards or one furlong length was probably not a chance decision. The basic dimension of 11 yards run through the Fibonacci sequence of 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 is 220 yards or one furlong.

Concluding Comment

“The want of a public park at West Bromwich has long been felt and would indeed be a great boon to the hardy sons of toil whose life it is to dwell here.” [Reuben Farley to the Earl of Dartmouth]

It is unlikely that today’s visitor to Dartmouth Park would recognise the Avenue as either a work of art or as a mathematical conundrum. Or even as something of an enigma within the overall ‘natural’ ambience of the rest of the Park. The appearance of a particular landscape changes over time, it matures and moves further and further away from the intentions of its original designers. Dartmouth Park now appears more natural than originally intended, and this conceals the social and cultural agendas of its first authors and commissioners.

It is more than likely that the meaning and associative possibilities that may underpin the original design of Dartmouth Park are today obscured by our mass media induced need for the immediately intelligible. And anyway, a park is just a park. Isn’t it?

The idea of a public park today is still to do with social responsibility, citizenship and neighbourliness, and we still visit parks to be active or to reflect. We still need, as Woollaston said, the opportunity “to delight and invigorate [ourselves] whilst moralizing on the beauties of nature…”. Good design still engages with these issues. Particularly so in the context of the Heritage Lottery Fund’s ‘Parks for People’ restoration and regeneration programme.

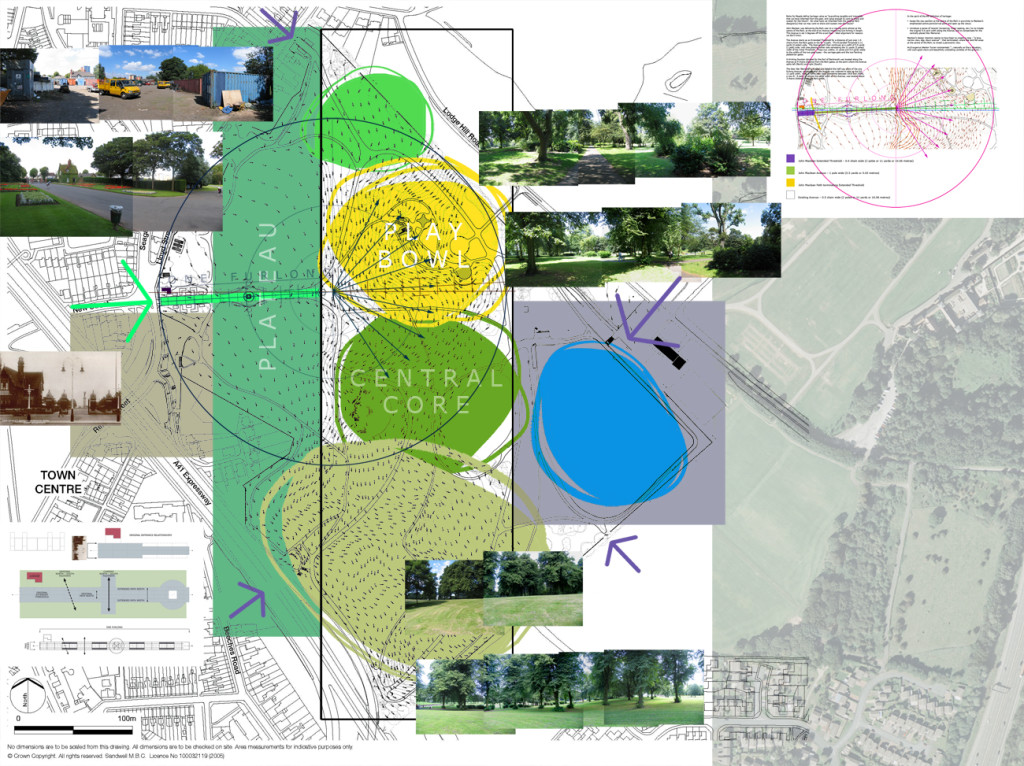

So how did David’s fascinating research inform the design process?

The context of the site within the trees and established access routes was an important reference for us and we felt that the building form should have close references to nature as was the original intention with the design of the Park.

The original Refreshment Room contained an ‘…upper chamber or observatory, from which a delightful and extensive view, not alone of the park, but also of the surrounding country for many miles may be obtained’. We felt that it was important to reinstate this experience in some way as the views, not only from the Refreshment Rooms but also along the North / South ridge line, were vital to the original experience of the park.

Our newly obtained knowledge of the Park’s history played an important part in the precise location of the new pavilion. During the feasibility study, we highlighted a total of 5 options for the siting of the building, but through consultation with local community groups, and using David’s detailed research of the history of the design of the park, it was agreed that visitors to the Park would travel down the Avenue and take the right fork in order to arrive at the Pavilion. The design of the building, with its spiralling walkway wrapping around the outside of the building ensures visitors still have a sense of the outdoors, and should ultimately reward them with a virtuous view across the Park.

“…what is truly good can only be obtained through hard effort…”

Additionally, the proportions of the turns in the walkway around the pavilion acknowledge the proportions of the existing Avenue, which follow the Fibonacci sequence. The dappled light through the timber walkway, reminiscent of walking through trees, ensures the building feels part of the surrounding landscape.

“This moving through (driving or walking) what appears to be a ‘natural’ landscape is at the core of the English landscape aesthetic, and clearly guides Maclean’s design for Dartmouth Park…”

Read more about Dartmouth Park Pavilion over here or click this link for a walkthrough video around the Pavilion. David’s full research piece including notes and other links can be viewed on his website.

History of Dartmouth Park

In 1876 land owner the Earl of Dartmouth, following a request by Alderman Reuben Farley, originally rented the land for the park to the West Bromwich commissioners, with the park being designed as a result of this action, so that workers would have somewhere ‘to delight and invigorate’, away from the factories.

The original park cost in excess of £12,623, was 56 acres and opened in 1878 but was soon extended by 9.5 acres to include a boating pool.

Over the next forty years new additions were made within the existing boundary and included 104 new trees added for Queen Victoria’s jubilee, a new Bowling Green, tennis courts and paddling pool, and the town’s war memorial in 1923.

By the 1970’s however, the park had begun to seriously decline. West Bromwich’s Northern Loop Road (The Expressway) had all but cut it off from the town centre and very little money was being invested. The refreshment room closed and eventually fell victim to arson. It was eventually demolished as was the former boathouse and bandstand.